Should you straighten your afro hair?

23.09.2009 in BLACK AFRO-CARIBBEAN HAIR LOSS![]()

With Michelle Obama in the White House and Tyra Banks ripping out her weaves on TV, the issue of how black women wear their hair is more contentious than ever. Hannah Pool takes on the politics of weaves, wigs and relaxers

Tyra Banks appeared on her TV show without her weave, saying ‘This is me y’all!’ Photograph: Amanda Schwab/Rex Features

“This is me, y’all!” exclaimed model, television host and businesswoman Tyra Banks on the set of her eponymous show, one day earlier this month. “I’ve just stepped out of the shower,” she said, to considerable screams of excitement from the (largely female) studio audience. “I wanted to show the real me, I wanted to show the raw me.” Given the shrieks and level of hysteria from her audience (and the response later on the blogs), you’d be forgiven for thinking Banks was standing there naked that day. In fact it was just her hair that was naked, or “real” as she called it.

Like many black women in the limelight, from Beyoncé to Naomi Campbell, Banks has worn weaves, wigs and hair pieces for pretty much all of her professional life – close to 20 years. In fact, it has been so long since anyone has seen Banks without a weave that one of her reasons for chopping the thing off was to dispel the rumours that she was bald underneath. “Because I wear weaves and wigs a lot of the time, a lot of people suspect that my real hair is jacked up,” says Banks in her new online magazine. But rumour-busting wasn’t her sole motivation for ditching the false hair; she was sick of the fakery, she said. After all this time, she wanted to see what her real hair felt like, what it looked like, and she wanted the rest of the world to see it too.

The extraordinary lengths black women go to, to achieve long flowing hair has long been something of a guilty secret within the black community. Even black men have often been kept in the dark about what exactly goes on in an afro hair salon, and precisely how much it costs. But all that’s changing, and fast.

Next month, comedian Chris Rock will blow wide open the multibillion-dollar black hair industry in his new documentary, Good Hair. The film, which won a special jury prize when it premiered at this year’s Sundance film festival, was inspired by Rock’s young daughters asking him why they didn’t have “good hair” (ie straight hair). This set Rock off on a journey to the heart of the secret world of weaves, wigs and relaxers.

The film comes at a time when, thanks partly to Banks, but mainly to Michelle Obama, the topic of black hair has been straying with increasing frequency into the mainstream media. “Because of Michelle being in the spotlight, there is this increased interest in how black women style themselves,” says Ingrid Banks, associate professor of black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “People are beginning to see the complexity of racial and gender politics that black women face daily.”

The debate over how black women wear their hair started early in the 20th century. It is no coincidence that Madam C J Walker, often referred to as America’s first self-made female millionaire, made her name selling hair products to black women. Walker, who was the first member of her family to be born free, started selling her home-made hair-loss remedy door-to-door in 1900. By 1917 she was at the helm of the largest black-owned business in America. More than 90 years later, black women spend, on average, three times more than white women on their hair.

These days, black hairstyles can be loosely divided into three categories. First there are natural styles, where the hair has been styled but left in its virgin state – afros and braids, for example. Then there’s processed hair, which has either been pressed, hot combed or chemically relaxed (ie the curl has been straightened to some degree), and finally there’s the world of weaves and wigs.

Of course it’s not just black women who wear weaves. But the big difference is that when white women pile on the extensions, no one accuses them of self-hatred, of trying to be something they’re not. For black women, opting for anything other than a natural style is still seen by many as a political act, a sign of having sold out, or worse, as a sign of some deep-seated desire to be white. And that is why, when a woman such as Tyra Banks steps out from beneath her weave, it means something. Hence the controversy when the New Yorker ran a cover illustration which put Michelle Obama in an afro to portray her as a militant black woman. The fact is, Obama with an afro would be a massive thing, a huge statement.

“After all this time, people read statements into how we wear our hair,” says Mikki Taylor, beauty and cover director at African-American monthly Essence, which has a readership of more than eight million. “That’s unfortunate. Some days if you want to wear your hair curly, why can’t that just be it? It’s got to be, oh what are they trying to say?” Taylor styled Obama for the magazine’s cover interview in May. They went for a “smooth bob”: “It’s the image of effortless chic that we wanted to present.”

Does Taylor think that Obama’s hair really matters? “It definitely matters. She is an inspiration to women of African descent. People watch her very closely.” Would she like to see her opt for a natural style, an afro say, or braids? “We embrace her as Michelle Obama, however she wears her hair.”

“If Michelle decided to have an afro people would probably have a heart attack,” points out Grammy award-winning singer Jody Watley, who featured in Vogue Italia’s Black Issue last year. “But she has the right to wear her hair however she wants. It is nice that she makes the natural statement through the girls. But I love her hair in the style she wears it. It looks very healthy, it’s a great cut. If she wore an afro I think it would be cool, she’d look hot, but I don’t think, oh, it’s too bad she’s not making that statement. People make too much of big deal about that.”

UK pop star Jamelia agrees: “If she shaved off one side of her hair and dyed it blond, I wouldn’t feel any differently about her.” Jamelia made a television documentary last year investigating where the hair for weaves and hair extensions comes from. “I saw some harrowing things,” she says. “People pay up to £2,500 for a weave with Russian hair but the women at the other end don’t benefit much from it. They were selling their hair for £100 at the most, and some would sell it for £4 . . . I no longer wear weaves personally, but professionally I do end up in a situations where it’s expected. I’m not against weaves, but I just feel a bit uneasy about it.”

Fellow soul singer Beverley Knight balks at the notion that black women who straighten their hair, or wear weaves, are in some way ashamed of their ethnicity: “If there’s one thing that will raise my hackles, get my back up and make me angry, it’s that particular assertion. There is nothing more insulting, degrading and malevolent than to throw that in the face of someone,” says Knight. “It’s just a hair choice, nothing more, with no other connotations.”

It is a just a hair choice, but it’s not necessarily an easy one to make against this politicised background. In July of last year I had my own straight-hair moment. After seven years of wearing an afro, I wanted to change my look. I’d done as much as I could with my afro; grown it, cut it, dyed it, pinned it, brushed it out, worn it tidy, worn it messy. I’d run out of ideas. I was bored with my ‘fro, and I was ready for something completely radical . . . Suddenly I found myself wondering if, perhaps, now was the time for me to try straight hair?

I set myself some boundaries: I would not chemically relax my hair, but have it dried straight. This is less traumatic for the hair; it is also temporary (on my hair it lasts up to four weeks, or until the hair gets wet). I would aim to wear it straight for a year (I have dried my hair straight once before but it was such a shock I only lasted a weekend, and only saw three people, so that hardly counts).

Then I asked my 21-year-old cousin Showhat to straighten my hair for me. Like many young women she is a master with the ceramics. We were in Sweden for a wedding, and my logic was that if I truly hated it I could wash it and return to London with no one any the wiser. But I didn’t hate it; in fact I rather liked it. It felt sleek and modern. My hair was bouncy and shiny, it looked healthy and, best of all, it moved. It even swished from side to side.

There was only one problem: it made me feel guilty. I felt like a traitor. And I became mildly obsessed about what signals I was sending out. If an afro says, “I’m confident enough to wear my hair as it comes,” what does wearing my hair straight say?

But after a few days I started to notice some unexpected side-effects of straightening my hair. Other Eritreans and Ethiopians – who generally all straighten their hair – started to nod and smile at me in the street, acknowledging me as one of them. And I love it.

And because my hair is dried straight, it needs redoing every three or four weeks – sooner if it rains. As a result, I am working my way through London’s east-African hair salons. With names like Sheba and Sisay, they are a world away from the west-end salons I used to visit, where I’d be lucky if one of the hairdressers specialised in afro hair. Pretty much all the clientele is of east African origin, usually from Ethiopia, Somalia or Eritrea, and they welcome me as if I am an old friend. Instead of feeling awkward and anxious when I sit in the hairdresser’s chair (will they know what do with my hair?), I feel as if I have gained access to an exclusive club.

All in all, the experience of wearing my hair straight over the last year has led me to change how I think of black women with straight hair. I realise how reductive it is to criticise a woman for going straight. I am still not a fan of relaxers, because I know how much they damage the hair. But I understand why so many black women do it. I understand the versatility of straight hair, and I understand the seduction of it. That said, I still wish more black celebrities wore their hair in natural styles, and I still have fantasies about Michelle Obama rocking an afro in the White House.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/sep/18/straighten-afro-tyra-banks/print

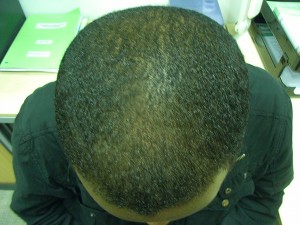

Do you have Hair Loss Problems, read our Hair Loss Help

no comment